The thyroid gland and its hormones play a fundamental role in regulating our metabolism and other vital physiological processes.

But the stressors of modern life mean that thyroid dysfunctions like Hashimoto’s and Graves’ disease have become more common.

Psychological stress, harsh dieting, sleep loss, and other factors, all have a significant negative impact on thyroid health.

Understanding the key signs of thyroid issues and how to optimise its function is vital to improve your body, your gym performance and your long-term health.

So here we look at why thyroid health is important, the main things that affect thyroid function, key symptoms of thyroid issues, and the steps you can take to maximise the health of your thyroid.

Why is thyroid health important?

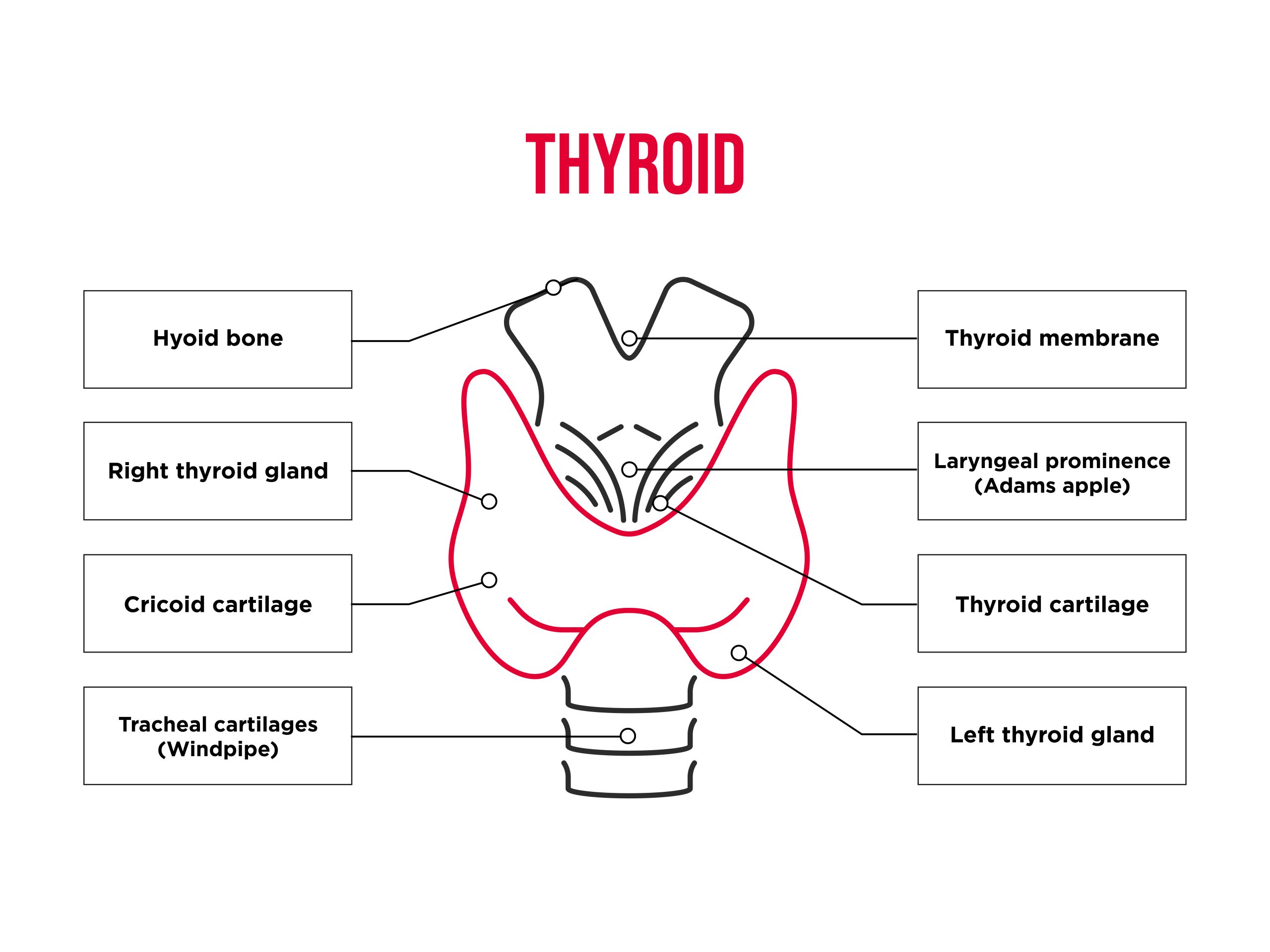

The thyroid is a butterfly-shaped gland situated at the bottom of the throat in front of the trachea and below the voice box (larynx). It produces three key hormones:

- Thyroxine (T4). The inactive form of thyroid, which must convert to T3 to become active. It stimulates metabolism and binds to receptors in most of the body’s cells.

- Triiodothyronine (T3). The active form of thyroid hormone.

- Calcitonin. Involved in helping to regulate levels of calcium and phosphate in the blood.

These hormones are responsible for regulating metabolism as well as:

- Basal body temperature

- Skin moisture

- Blood pressure

- Promoting tissue growth

- Secreting digestive juices

- Managing levels of oxygen, calcium and cholesterol in the blood

- Metabolising all macronutrients

Evidence shows that T3 may improve aerobic health through enhancing mitochondrial function[4],[5].

Mitochondria are organelles within each cell in the body that are crucial for ATP production. As a result, improved mitochondrial function improves the body’s capacity for energy output, which of course, has a significant impact on both your results and quality of life.

The role of T3 is so important that low thyroid hormone levels are often interpreted as a cardiovascular risk factor[6].

If any of these hormones become inactive, are produced in insufficient amounts, or do not communicate with one another effectively, your basal metabolic rate (BMR) may drop significantly. In patients who have undergone thyroidectomy, which involves the removal of the thyroid gland, BMR can decrease by up to 40%[7].

Research has consistently demonstrated links between T3 levels and body composition. In one study, seven healthy human males took a low dosage of exogenous T3 for six weeks. At the end of the trial, the researchers found an average change in body composition, with a three-to-one split between fat loss and muscle loss[8]. While the sample size was small, this research implies that optimising thyroid output significantly impacts body composition.

Improving thyroid health can dramatically improve your body composition and health.

What affects thyroid health?

Thyroid function can become unbalanced by a variety of factors, including:

1. Growth hormone

Growth hormone increases the rate at which T4 converts to T3. Studies of adult male rats have shown that induced states of hypothyroidism result in a broad suppression of stored growth hormone stored and decreased conversion to T4 to T3[9].

2. Stress

It is important to distinguish between two types of stress: acute and chronic. Acute stress is sharp, short burst of stress, i.e., being chased by a tiger. In a modern scenario, this might look like a heavy weight training session, followed by a more relaxed state. We are well evolved to react and adapt to these kinds of stressors.

Research suggests that acute stress positively affects the conversion of T4 to T3 by increasing adrenaline and noradrenaline and creating a demand for fuel[10]. This could, in part, lead to a slight up-regulation in energy expenditure after weight training and high-intensity exercise.

Chronic stress is severe and persistent, such as the continual, ongoing pressures of modern life, dietary choices, alcohol, poor sleep, and work and relationship stress. Chronic stress appears to damage the hippocampus in the brain, which controls learning and memory[11]. We are not well adapted to chronic stress.

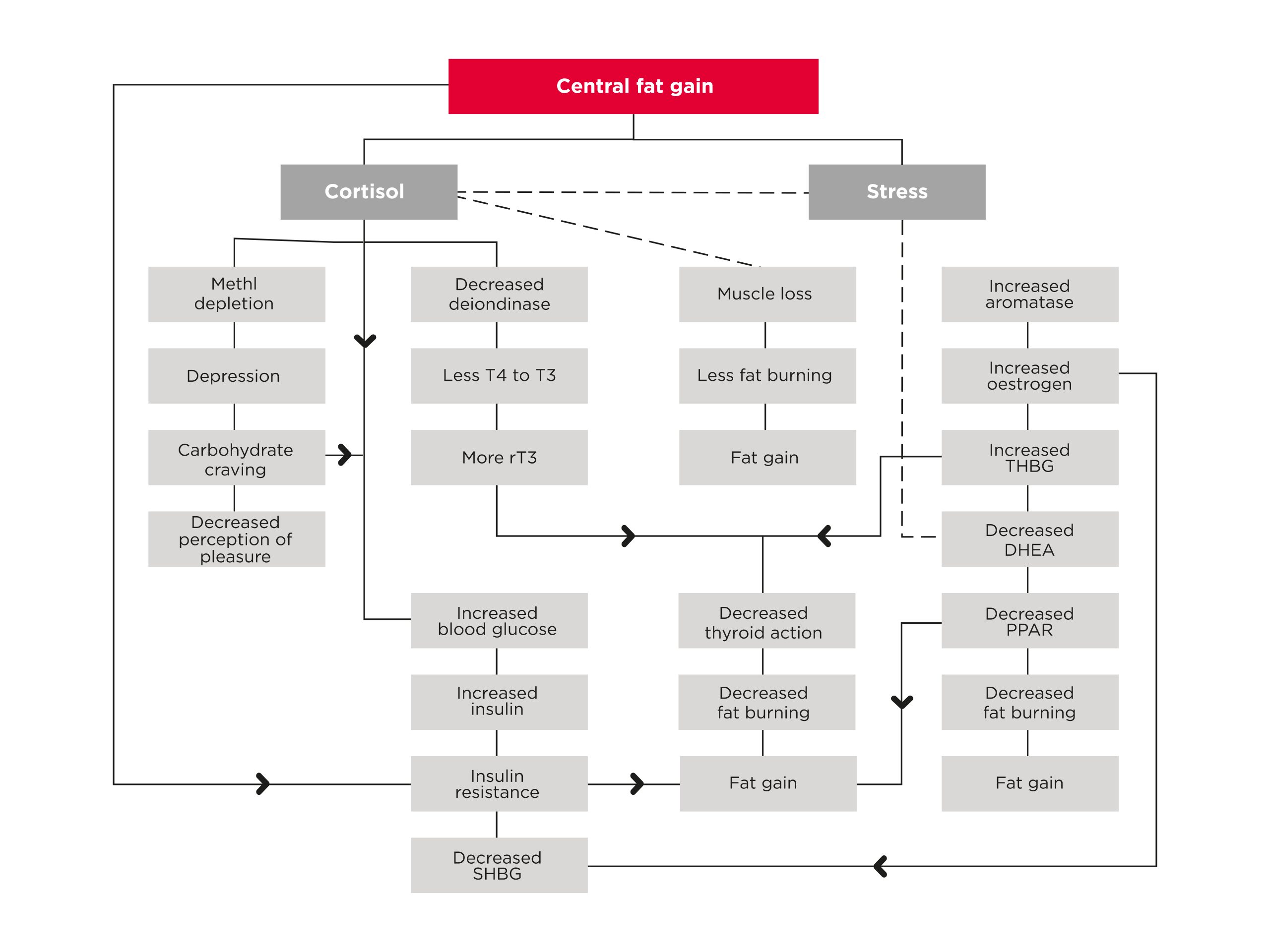

Chronic stress slows down the conversion of inactive thyroid to active thyroid via an enzyme called thyroxine 5-deiodinase (it removes iodine); this also increases the production of reverse T3, leading to decreased thyroid function.

Stress increases the amount of thyroid hormone-binding globulin that binds to the thyroid hormone and prevents it from being active. This is likely due to the body downregulating non-essential functions in an attempt to fight chronic stress.

The effects of chronic stress on thyroid output.

3. Prolonged low-carbohydrate dieting

Carbohydrate intake can also affect thyroid function. One potential reason is that higher levels of circulating blood glucose may increase blood temperature. Another factor is that increased glycogen levels in muscle cells improve training performance, and higher carbohydrate intake reduces the body’s chronic stress response.

Research suggests that we need anywhere from 50-120 grams of carbohydrates to prevent a dramatic decline in T3 during low-carbohydrate dieting phases. This decline increases further if these low-carbohydrate periods become prolonged[12],[13],[14],[15].

4. Nutrient deficiencies

Many nutrient deficiencies can interrupt the process governing the secretion and conversion of hormones that enable the thyroid to function optimally, including:

Zinc

Zinc deficiency is incredibly common in the western world and can lead to decreased production of TRH. Zinc also plays a role in the conversion of T4 to T3.

Zinc is typically found in oysters, red meat, and poultry are excellent sources of zinc. Beans, chickpeas, and nuts (such as cashews and almonds) also contain zinc.

Vitamin E

Vitamin E has a cellular effect on the thyroid gland, along with the adrenals and pituitary gland. Rodent studies have consistently demonstrated that vitamin E increases levels of T4 and T3 as well as TSH[16].

Vitamin E is typically found in sunflower, safflower, and soybean oil, sunflower seeds, almonds, peanuts, peanut butter, beet greens, collard greens, spinach, pumpkin, red bell pepper.

Selenium

Selenium acts as a catalyst to convert inactive T4 to the biologically active T3 and protect thyroid cells from oxidative damage. Studies suggest that supplemental selenium could alleviate the toxic effect of excessive iodine intake on the thyroid[17].

Common sources of selenium include Brazil nuts, tuna, oysters, pork, beef, chicken, tofu, whole wheat pasta, shrimp, and mushrooms.

Ashwagandha

Ashwagandha is an extract typically taken from the berries or roots of the plant and can only be obtained through supplementation. Ashwagandha is crucial for the healthy conversion of T4 to T3 and helping dampen the chronic stress response. Ashwagandha is one of the key ingredients in U.P.’s Inflammation Support, alongside resveratrol and longvida curcumin, which are also powerful anti-inflammatories.

While supplementation can sometimes be useful, it is important to be mindful that this is not always the case. For example, two nutrients that help form thyroid hormones are tyrosine and iodine. Supplementing with tyrosine may provide a slight benefit to thyroid output. However, iodine supplementation has been shown to have no significant benefit and may negatively impact thyroid function in low-carbohydrate diets[18].

5. Gender differences

Women are more prone to dysfunctional thyroid issues than men. This is likely down to women’s higher levels of oestrogen, which decreases levels of T3, and progesterone, which increases levels.

Women are more prone to thyroid dysfunction than men.

What are the symptoms of thyroid problems to look out for?

Many symptoms of thyroid issues improve with lifestyle and dietary changes but if you are concerned about your thyroid health, always refer to a relevant specialist.

Some common symptoms of hyperthyroidism include:

- Difficulty sleeping and disturbed sleep

- Anxiety

- Dramatic weight loss

- Heart palpitations

- High blood pressure

- The feeling of overheating

- Sweating (beyond normal levels)

Common symptoms of hyperthyroidism include:

- Muscle pain

- Slow wound healing

- Fatigue

- Weight gain

- Depression

- Constipation

- High cholesterol

- Low body temperature

- Thinning facial and body hair

- Dry skin

- Brittle nails

- Alopecia

- Cold extremities

- Low morning temperature

If you experience any of these symptoms, refer to your healthcare provider, who may refer you to an endocrinologist for further testing and diagnostics.

Thyroid diseases you should know about

Some diseases can interfere with thyroid functioning, including:

1. Graves’ disease

Graves’ disease is an immune response that triggers hyperthyroidism, the overproduction of thyroid hormones. It is caused by an autoimmune dysfunction where the body produces abnormal antibodies that target the thyroid gland cells. These antibodies mimic the hormones sent by the pituitary and bind to the receptors of the thyroid gland. What this means is that the thyroid gland is permanently activated. This overproduction of antibodies can lead to chronic inflammation.

2. Hashimoto’s disease

Hashimoto’s disease is an autoimmune condition that causes the body to produce antibodies that attack and damage the thyroid gland. This lowers overall thyroid function, leading to hypothyroidism. If left untreated, it can lead to severe problems, including the common symptoms of hypothyroid and complications during pregnancy for women.

Hashimoto’s is more common among women than men, generally between 40 and 60 years old, but can also occur in teenage girls. It is often genetic, and those with type I diabetes, anaemia, B-12 deficiencies, arthritis and celiac disease are more likely to develop Hashimoto’s disease.

Maximising your thyroid health

While the mechanisms underpinning thyroid regulation may be complex, lifestyle factors, including stress management, are crucial in optimising your metabolic health.

1. Effective stress management

Whether you choose to meditate, journal or set aside time for self-care, prioritising relaxation and recovery is vital for maximising thyroid health through its positive effects on cortisol.

2. Prioritise sleep

Circadian rhythm appears to have a crucial role in regulating thyroid output[19]. While acute sleep loss increases the release of thyroid-stimulating hormone from the pituitary, consistent sleep deprivation of as little as three hours results in significant declines in TSH and free T4, particularly in women[20]. If you are concerned about your thyroid health or have been diagnosed with a thyroid condition, try to ensure you sleep for at least 7-9 hours and maintain a regular sleep schedule.

3. Limit periods of harsh, very-low-carbohydrate dieting

Research into very-low-calorie diets indicates that while T4 levels remain relatively stable during periods of severe caloric restriction, T3 levels decrease. This effect appears to be even more pronounced in low-carbohydrate compared to high-carbohydrate diets[21]. If you are dieting and concerned about your metabolic health, aim either for a slower rate of change (anywhere between 0.5-1% of total body weight loss per week) and/ or schedule regular refeeds at maintenance calories to minimise physiological stress. It may also be advisable to favour a slightly higher split of carbohydrates relative to dietary fats.

4. Improve digestive health

Gut microbiota influences the uptake of minerals such as iodine, selenium, zinc, and iron, which are crucial to supporting thyroid function[22]. Gut dysbiosis (an imbalance in our gut flora), damage to the intestinal barrier and increased gut permeability often coexist in those with thyroid diseases such as Hashimoto’s and Graves’ disease[23]. However, intake of dietary fibre and their resulting short-chain fatty acids improve immune regulation and have an anti-inflammatory effect[24],[25]. Therefore, one vital perspective in managing thyroid health includes improving gut health through effective hydration, avoiding inflammatory foods and increasing intake of high-fibre vegetables. It may also be beneficial to track fibre intake closely. For men, this should be up to 30g per day and up to 25g for women.

5. Supplement

While supplementation alone cannot improve thyroid function, supplements can support proper diet, training volume and lifestyle habits, including:

L-Tyrosine, the key ingredient in Drive, helps form the backbone of the thyroid hormone. Dosages of around 100-150mg/kg of body weight taken around 60 minutes before exercise may help provide the raw materials of thyroid hormone and focus during training.

Contains zinc, which is important for the production of thyroid regulating hormone and aiding in the conversion of T4 to T3. Zinc NT also contains selenium, which is found in meat, fish and nuts. Supplementation is advisable if you follow a plant-based diet, N.T. Support provides essential neurotransmitters that help relieve the psychological effects of stress.

Observational studies have found correlations between low vitamin D levels and both hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism[26],[27]. It is not clear if low vitamin D is a cause, consequence or an unrelated factor in these conditions.

Low vitamin D levels reduce the immune system’s response, which may speed up the progression of thyroid disease. People with thyroid diseases may also have altered health or lifestyles that involve low levels of vitamin D. For example, patients with Gravesʼ disease may see an increased breakdown of vitamin D into inactive products. In contrast, those with an underactive thyroid may spend less time outdoors due to tiredness and thus have reduced sun exposure.

D3 Replenish provides vitamin D3 along with vitamin K1 and K2. Vitamins D and K are essential for many physiological processes, including cognitive functions, the immune system and general health and wellbeing.

Magnesium is responsible for converting the inactive T4 thyroid hormone into the active form of T3. This is extremely important because the metabolism of your body’s cells are enhanced by T3 rather than the inactive T4.

Magnesium deficiency is related to goitre or an enlarged thyroid gland.

Magnesium is vital for the production of T4 in the thyroid gland. Without magnesium, many of the thyroid enzymes that make thyroid hormones could not function.

Contains ashwagandha, resveratrol and longvida curcumin, all known to be powerful anti-inflammatories.

Ashwagandha is crucial for the healthy conversion of T4 to T3 and helping dampen the chronic stress response.

Vitamin B12 is especially important for older individuals and those eating a plant-based diet.

B Complex is specially formulated to create an optimal environment for activating B vitamins with the addition of trimethylglycine (TMG) and choline. Choline is a compound that directly affects the vagus nerve, which is responsible for regulating internal organ functions, such as digestion, heart rate, respiratory rate, vasomotor activity, and certain reflex actions, such as coughing, sneezing, swallowing, and vomiting.

Fish oil has been found to improve signalling in other bodily tissues, such as the liver, and reduce systemic inflammation.

Omega 3 Concentrate contains the two most important components of fish oil: EPA and DHA. Both help to improve depression, heart health and reduce liver fat, joint pain, inflammation and muscle pain.

The take-home message

The thyroid gland and its hormones play a fundamental role in regulating our metabolism and many other vital physiological processes. Unfortunately, the stresses of modern life mean that thyroid dysfunctions have become increasingly prevalent. However, lifestyle choices, particularly stress management and improving digestive health, are crucial avenues for ensuring optimal thyroid health and functioning. If you are concerned about your thyroid health or you experience any of the common symptoms of thyroid issues, refer to your health care provider or endocrinologist for further support.