Do you know what men and menopausal women have in common? They’re both at higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Why?

The answer lies in hormones and how the body stores fat when you eat too many carbohydrates.

Here we explore exactly why men and menopausal women are at greater risk of diabetes, its effects and how you can prevent your story from becoming another statistic.

What is type 2 diabetes?

Broadly speaking, diabetes mellitus is a disease that causes dysfunction throughout the body and alters how the body converts, stores, and uses carbohydrates.

If you have type 2 diabetes, you’re at significantly higher risk of serious medical concerns like stroke, heart attack and heart disease.

We all know that diabetes is a serious condition. But exactly what diabetes is and its effects are often poorly understood.

So, let’s have a quick rundown.

What’s the difference between type 1 and type 2 diabetes?

In simple terms, type 1 is something you’re born with or develop naturally; type 2 is entirely preventable and caused by modern, unhealthy lifestyles.

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease that causes the body to attack the cells in your pancreas that make the hormone insulin.

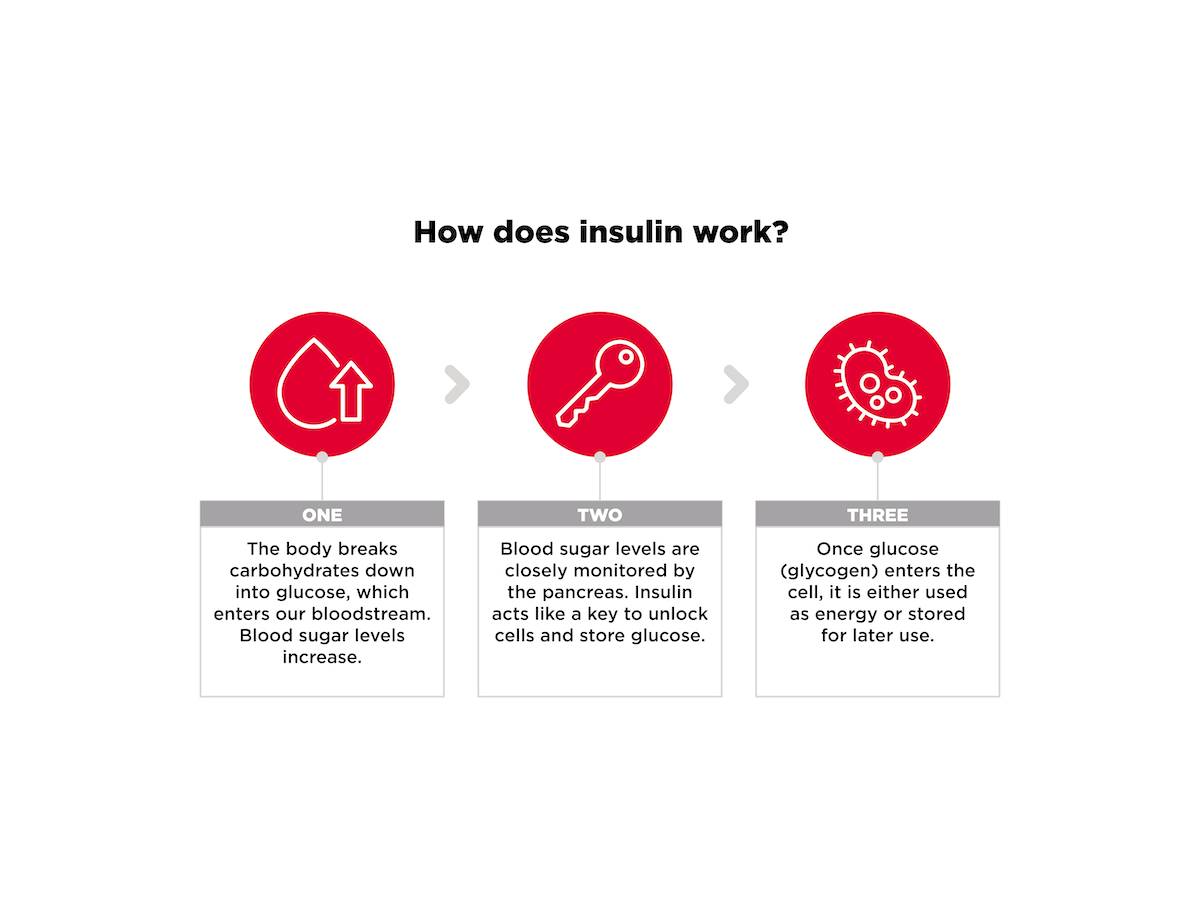

All hormones function similarly to a key in a lock – each one ‘unlocks’ specific sites around the body to perform specific functions.

When you eat or drink carbohydrates, the body breaks them down into glucose. Insulin’s role is to transport this glucose around the body and ‘unlock’ cells so it can be stored within them.

In type 1 diabetes, the body cannot produce enough insulin to meet demand. So, as glucose enters the bloodstream, insulin isn’t there to unlock these storage sites. Glucose then builds up in the blood stream, leading to dangerously high blood sugar levels.

Having too much sugar in the blood can damage the vessels that supply blood to vital organs, increasing the risk of heart disease, stroke, loss of sight and nerve problems.

Only 8% of people with diabetes in the UK have type 1 [1]

Type 1 only represents a very small proportion of total diabetes cases.

Whereas type 1 diabetes is mostly inherited, type 2 diabetes is considered a ‘lifestyle’ disease that is almost entirely preventable [2].

Who is most at risk of developing type 2 diabetes?

Now, you might think that diabetes is something that happens to other people. But you could be at bigger risk than if you fall into one of these six categories:

Being overweight or obese

Men with a waist over 94 cm or women with a waist over 80 cm are far more likely to develop diabetes than those with a healthy body composition [3].

Being aged 65 or over

Half of all people with diabetes in the United Kingdom are aged over 65 years and a quarter are over 75 [4].

High blood pressure or cholesterol levels

People with high blood pressure usually have poor insulin sensitivity, which means their bodies cannot manage blood sugar levels. As a result, they are at increased risk of developing diabetes compared to those with normal blood pressure [5].

A family history of diabetes

You are four times more likely to develop diabetes if someone in your family has it. These odds are even higher if you have three or more diabetic relatives [6].

Being physically inactive

Low physical inactivity and poor physical fitness are significant factors in developing type 2 diabetes.

Leading an unhealthy lifestyle

Chronic stress, poor sleep, alcohol intake and smoking have all been linked to type 2 diabetes [7], [8], [9], [10], [11].

Men vs women: who is more at risk?

Figures show that obesity rates are similar between the sexes, yet men are 50% more likely than women to develop type 2 diabetes [12], [13].

The World Health Organization’s latest major report estimates that obesity is now at ‘epidemic proportions’ in Europe [14].

But if the sexes are becoming fatter at similar rates, why are men more so much more vulnerable?

Here’s where it gets interesting.

What happens when you eat too many carbohydrates?

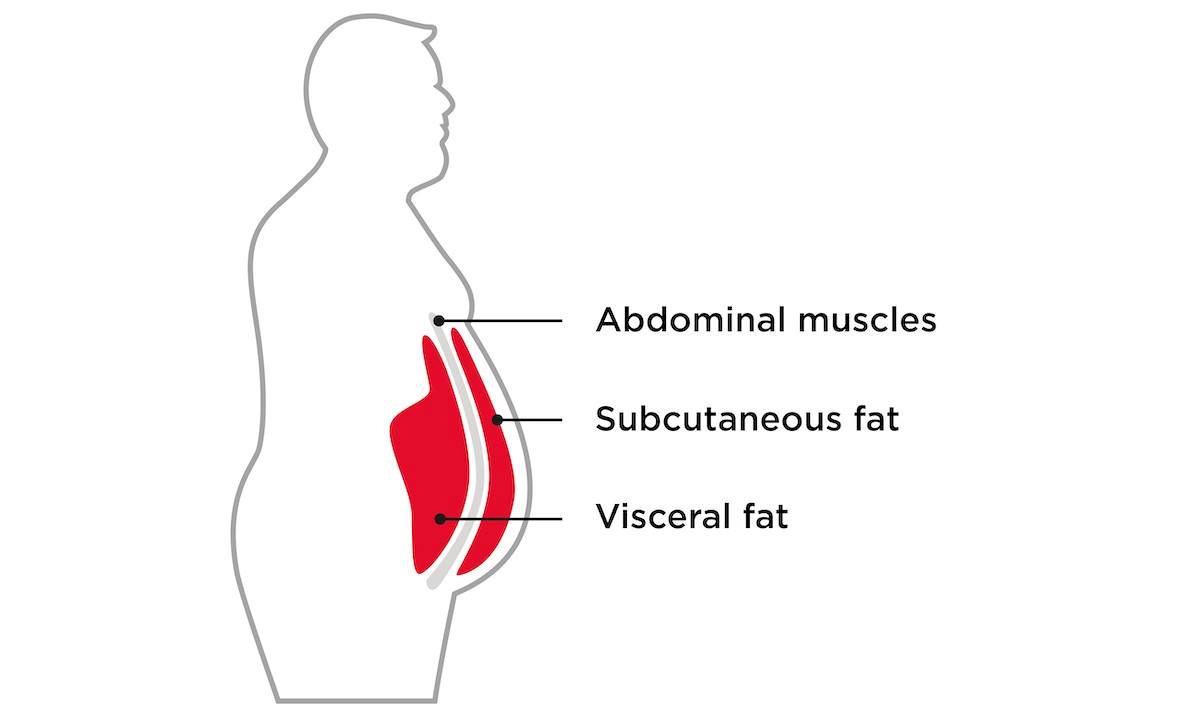

When our calorie intake consistently exceeds our energy requirements over days, months and years, dietary fat is stored directly in one of three areas: under the skin, viscerally (around our internal organs) or in the liver.

But when we eat carbohydrates, the body does something different.

Under normal circumstances, carbohydrates are either used as fuel or stored in muscle cells if they aren’t needed. The problem is that once your muscle cells are full, excess carbohydrates go to the liver where they are converted to fat via process called lipogenesis.

This new fat can be sent around the body as ‘very low-density lipoproteins’ (which are transported around the body by cholesterol), used for energy, or stored in your now very full liver.

But it’s what happens next that is the dangerous part…

Lack of exercise could literally be killing you

This process of lipogenesis is stimulated by insulin. But if you are ‘insulin resistant’ (caused by a poor diet, inactivity, poor sleep, high stress, and so on) levels of insulin circulating the body are much higher. Effectively, insulin has nowhere to go and these high levels mean the process of creating and storing liver fat ramps up significantly [15].

And this entire process takes far less time than you might think.

In one study, participants were asked to eat a bag of sweets, drink a 300ml bottle of full-sugar Pepsi and 30 ml of fruit juice daily, in addition to their normal food. After just three weeks, the volunteers all saw their liver fat content increase by almost a third [16].

So how exactly does this relate back to diabetes?

The answer lies in the role of fat…

Fat is actually a pretty smart organ

Fat is not simply an unsightly appendage hanging over your jeans that ruins the effect of your otherwise god-like body. It’s a complex organ that fulfils several functions in the body, including managing our hunger levels [17].

Researchers have also found that visceral fat secretes a type of protein that may increase insulin resistance [18]. Poor insulin management leads to more visceral fat, which further decreases insulin sensitivity, creating a vicious cycle.

And the risks don’t stop there.

Some visceral fat is essential to protect our internal organs. But when more than 10% of our total fat is held viscerally, our risk of type 2 diabetes rises dramatically [19]. The risk of breast cancer, Alzheimer’s, heart disease and colorectal cancer all increase too [20].

So, why do men and women experience this risk differently?

Well, it all comes down to a little hormone called oestrogen…

Oestrogen protects against diabetes

Most women probably associate hormones with periods and wanting to eat everything in sight. But there are a tonne of reasons that a healthy oestrogen balance puts women at an advantage when it comes to diabetes.

Oestrogen has a two-way relationship with visceral fat; the more oestrogen you have, the greater the amount of fat stored under the skin. When oestrogen is low, the more fat you will store viscerally [21].

Of course, before the menopause this is a big advantage.

Oestrogen also increases the number of fat-storing cells in sites like the breasts, hips, back of the arms and thighs – effectively away from the trunk and that all-important danger zone [22].

Unfortunately, this is where the men draw the short straw…

Men have more visceral fat

While men on average have less fat, their hormonal profile makes them more likely to more fat around the trunk and internal organs. And as testosterone levels decline with age, this becomes even more probable [23], [24].

And that’s not even to mention the fact that men are less likely to follow a healthy diet and lifestyle or seek medical care [25], [26], [27].

Sorry fellas, the stats don’t lie.

Men are also more likely to be overweight, smoke and to drink excessively, all key risk factors for developing diabetes [28], [29], [30].

But ladies, don’t rest on your laurels either…

The risk of type 2 diabetes increases after menopause

Women have the upper hand before menopause but afterwards, it’s a different story.

The complete cessation of oestrogen production at menopause destabilises blood sugar levels, leading to weight gain, and increased insulin demands [31].

Menopausal women with diabetes are also more likely to experience more severe symptoms like hot flashes and night sweats [32].

What are the risks of type 2 diabetes?

You might not have yet made the link between that Friday night take-away or the couple of pints you had down the pub last night.

But type 2 diabetes is a condition that comes with a major health warning, affecting nearly every part of the body.

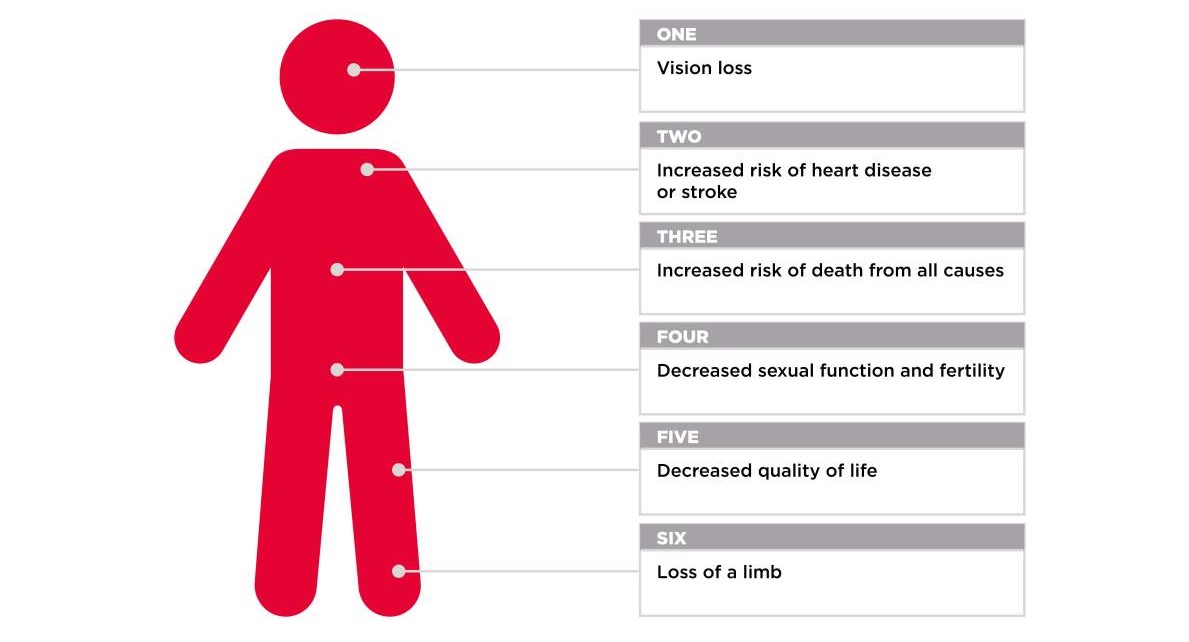

1. You will die younger

On average, diabetic people die ten years earlier than healthy adults [33].

If you are unlucky enough to have a limb amputated, these figures are even more stark.

Only 41% of people who have a diabetes-related amputation survive for five or more years after surgery [34].

2. Your risk of dying from heart disease or stroke rises astronomically

If you have type 2 diabetes you are three times more likely to die from stroke and five times more likely to die from heart disease than a healthy adult [35].

Women with diabetes are twice as likely to experience cardiovascular disease than diabetic men. Women also have worse outcomes after a heart attack and are at higher risk of other complications such as blindness [36], kidney disease [37], and depression [38].

3a. Decreased sexual function and fertility – In women

Women with type 2 diabetes find it harder to conceive and when they do, their risk of miscarriage, stillbirth, preterm birth [39], and caesarean section delivery all increase too [40].

Gestational diabetes (GD) occurs when the mother cannot produce enough insulin for her and her baby. Women who are overweight, obese, or have a family history of type 2 diabetes are most likely to develop GD. GD usually goes away after pregnancy, but around 50% of women also develop type 2 diabetes [41].

Women may experience more severe PMS and heavier, longer periods, and urinary tract infections (UTIs) may become more frequent [42].

3b. Decreased sexual function and fertility – In men

If you’re a man with type 2 diabetes, expect your sex drive to plummet. Up to 75% of men with type 2 diabetes experience ED at some point [43], [44]. This is thought to be caused by damage to the nerves and blood vessels in the penis from uncontrolled blood sugar [45], [46].

4. You could lose a limb

As many as one in four people with diabetes also develop diabetic foot ulcers [47]. A shocking 60% of non-traumatic lower-limb amputations worldwide result are caused by diabetes-related complications [48].

5. Decreased quality of life

Having to rely on others to do simple tasks like doing your weekly food shopping, needing help to shower, get dressed or put on your shoes; this is the reality of unmanaged type 2 diabetes.

Statistics consistently show that scores for quality of life, life satisfaction and mental health all take a major hit in those with diabetes [49], [50]. Those with type 2 diabetes also see their risk of suicide rise by more than 85% [51].

6. You could lose your sight

Uncontrolled blood sugar levels can cause irreversible damage the blood vessels in the delicate tissue at the back of the eye (your retina).

Dark spots in your vision, blurred or fluctuating vision and even vision loss are all tell-tale signs. However, these symptoms only appear after irreversible damage has been done.

Sight loss and damage is one of the most common complications from diabetes and is also the leading cause of blindness in the western world [52].

The good news is that, whatever your gender, these risks can be avoided through diet and exercise.

And if you’re thinking that you’ll never get to see a carb again in your life, think again.

How can you minimise your risk of diabetes?

1. Maintaining a healthy body composition

The primary cause of diabetes is excess body fat, so losing weight is the most effective way to cut your risk.

Even short-term reductions can improve your body’s ability to regulate blood sugar levels. Research shows that for every nine kilos you lose, your risk of developing diabetes drops by 11% for men and 17% for women [53].

Achieving a healthy body composition can even reverse diabetes altogether [54].

2. Clean up your diet

Diabetes affects your body’s ability to process and store carbohydrates effectively. But that doesn’t mean that they are off the menu forever.

Going low carb initially may help to give your fat loss attempts a head start.

High-fibre foods like cruciferous vegetables (broccoli, cauliflower, green beans, cabbage, etc) boost your body’s ability to balance blood sugar levels, manage appetite and improve digestive health. All of these can indirectly assist in weight loss.

When you are ready to start reintroducing starchy carbohydrates, go for whole, unprocessed foods, such as root vegetables and wholegrains, which are rich in nutrients as well as fibre.

Pairing this with a high-protein diet encourages the body to tap into fat stores, not muscle. And the more muscle you have, the better your body can utilise carbohydrates. Eating between 2.2-2.8 g of protein per kg of lean body mass is a good place to start for most people.

3. Start lifting

All exercise reduces your risk of diabetes, but if you want to turbocharge your results, resistance training can help nearly every problem caused by diabetes.

Poor body composition – when you have low levels of muscle and a proportionately high amount of body fat – ramps up your risk of type 2 diabetes, even if you’re not obese [55].

The hands-down, undisputed, most effective way to reverse this? Resistance training.

Regular weight training improves your body’s ability to lose weight, manage blood sugar levels and build and retain muscle, which itself can help to sustain successful weight loss [56].

4. Get moving

Find a form of activity that you enjoy and run with it (literally!).

It doesn’t matter what you do, simply increasing how much you move on a daily basis is a critical first step [57].

Whether you enjoy a morning stroll, a group exercise class or going for a swim, regular, intense exercise could cut your chances of developing diabetes by up to 55% [58].

For most people, a combination of a daily step goal (10,000 steps is a good benchmark to start) and resistance training two to three times per week is a magic recipe for success.

5. Manage your sleep

High stress and poor sleep not only make you feel crappy, they also have several negative effects that make them big ‘no-no’s if you’re trying to optimise your blood sugar levels.

Sleep loss ramps up production of the hunger hormone ghrelin and reduces insulin sensitivity, making fat gain much more likely [59].

A recent study asked overweight subjects who normally slept for 6.5 hours to extend their time asleep by just two hours. The results showed that their average calorie intake decreased by an average of 270 kCal, without any prescribed diet or physical activity [60].

That’s roughly half the cut in calories you need each day to produce one pound of fat loss in a week, and that’s before you’ve even started to diet or exercise!

Making sure you sleep seven to nine hours per night is the quickest, most effective and cheapest way to immediately cut your risk of diabetes.

The take-home

Diabetes is on the rise globally and men and menopausal women are particularly vulnerable to this lifestyle disease.

But while there are some factors that aren’t within your control, you can take back the power to keep diabetes at bay through diet and exercise.

References

- Diabetes U.K. (2019). Type 1 Diabetes. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/diabetes-the-basics/types-of-diabetes/type-1 [Accessed 29.04.2022]

- Rodriguez-Saldana, J., (2019). The Diabetes Textbook. Springer.

- NHS (2019). Obesity. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/obesity/ [Accessed 05.05.2022].

- Croxson, S.C., et al. (1991). The prevalence of diabetes in elderly people. Diabetes Medicine, 8 (1), pp. 28-31.

- Petrie, J. R., Guzik, T. J., & Touyz, R. M. (2018). Diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease: Clinical Insights and Vascular Mechanisms. The Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 34(5), pp. 575–584.

- Annis, A. M., Caulder, M. S., Cook, M. L., & Duquette, D. (2005). Family history, diabetes, and other demographic and risk factors among participants of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2002. Preventing Chronic Disease, 2 (2), A19.

- Brugnara, L., et al. (2016). Low physical activity and its association with diabetes and other cardiovascular risk factors: a nationwide, population-based study. PloS one, 11(8), p.e0160959.

- Wei, M., Schwertner, H.A. and Blair, S.N., (2000). The association between physical activity, physical fitness, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Comprehensive therapy, 26( 3), pp.176-182.

- Surwit, R.S., Schneider, M.S. and Feinglos, M.N., (1992). Stress and diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care, 15 (10), pp.1413-1422.

- Knutson, K.L. and Van Cauter, E., (2008). Associations between sleep loss and increased risk of obesity and diabetes. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1129 (1), pp.287-304.

- Rimm, E.B., (1995). Prospective study of cigarette smoking, alcohol use, and the risk of diabetes in men. British Medical Journal, 310 (6979), pp.555-559.

- NHS Digital (2019). Statistics on Obesity, Physical Activity and Diet, England, 2019. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/statistics-on-obesity-physical-activity-and-diet/statistics-on-obesity-physical-activity-and-diet-england-2019/part-3-adult-obesity [Accessed 03.05.2022].

- Nordström, A., et al. (2016). Higher Prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes in Men Than in Women Is Associated With Differences in Visceral Fat Mass, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.101:10, Pages 3740–3746

- WHO (2022). WHO European Regional Obesity Report 2022.

- Taylor, R., (2013). Banting Memorial lecture 2012: reversing the twin cycles of type 2 diabetes. Diabetic Medicine: A Journal of The British Diabetic Association, 30 (3), pp. 267–275.

- Sevastianova, K., et al. (2012). Effect of short-term carbohydrate overfeeding and long-term weight loss on liver fat in overweight humans. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 96 (4), pp. 727–734.

- Shimizu, H., et al. (1997). Serum leptin concentration is associated with total body fat mass, but not abdominal fat distribution. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders: journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 21 (7), pp. 536–541.

- Chang, X., et al. (2015). Serum retinol binding protein 4 is associated with visceral fat in human with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease without known diabetes: a cross-sectional study. Lipids in Health and Disease, 14, 28.

- Harvard Health Publishing (2021). Taking aim at visceral fat. https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/taking-aim-at-belly-fat [Accessed 05.05.2022].

- Diabetes UK (2022). Visceral fat (active fat). https://www.diabetes.co.uk/body/visceral-fat.html [Accessed 05.05.2022].

- Brown, L.M, Clegg, D.J., (2010). Central effects of estradiol in the regulation of food intake, body weight, and adiposity. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 122 (1-3), pp. 65-73.

- Karastergiou, K., et al. (2012). Sex differences in human adipose tissues–the biology of pear shape. Biology of Sex Differences, 3(1), 1-12.

- Allan, C.A., et al. (2008). Testosterone therapy prevents gain in visceral adipose tissue and loss of skeletal muscle in nonobese aging men. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 93, pp. 139–146.

- Stevens, J., Katz, E.G., Huxley, R.R. (2010). Associations between gender, age and waist circumference. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 64, pp. 6–15.

- Martin S. (2002). Surprise! Women eat healthier than men. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal , 167 (8), pg. 913.

- Franceschi, C., et al. (2000). Do men and women follow different trajectories to reach extreme longevity?. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 12(2), pp.77-84.

- Banks, I. (2001). No man’s land: men, illness, and the NHS. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 323 (7320), 1058–1060.

- Fryar, C.D., Carroll, M.D., Afful, J., (2020). Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and severe obesity among adults aged 20 and over: United States, 1960–1962 through 2017–2018. NCHS Health E-Stats, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Higgins, S.T., Kurti, A.N., Redner, R., et al. (2015). A literature review on prevalence of gender differences and intersections with other vulnerabilities to tobacco use in the United States, 2004-2014. Preventative Medicine, 80, pp. 89-100.

- Kanny, D., et al. (2018). Annual Total Binge Drinks Consumed by U.S. Adults, 2015. American journal of preventive medicine, 54(4), 486–496.

- Jouyandeh, Z., Nayebzadeh, F., Qorbani, M. (2013). et al. Metabolic syndrome and menopause. Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders, 12, 1.

- Slopien, R., et al. (2018). Menopause and diabetes: EMAS clinical guide

- Diabetes UK (2010). Diabetes in the UK 2010: Key statistics on diabetes. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/resources-s3/2017-11/diabetes_in_the_uk_2010.pdf [Accessed 06.05.2022].

- Hoffmann, M. et al. (2015) Survival of diabetes patients with major amputation is comparable to malignant disease, Diabetes and Vascular Disease Research, pp. 265–271

- Diabetes UK (2010). Diabetes in the UK. London.

- Roglic, G., 2009. Diabetes in women: the global perspective. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 104, pp. S11-S13.

- Shen, Y., et al. (2017). Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for incident chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine, 55(1), pp.66-76.

- Pan, A., et al. (2011). Increased mortality risk in women with depression and diabetes mellitus. Archives of general psychiatry, 68 (1), pp.42-50.

- Negrato, C.A., et al. (2012). Adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with diabetes. Diabetology & metabolic syndrome, 4 (1), pp.1-6.

- Remsberg, K.E., et al. (1999). Diabetes in pregnancy and caesarean delivery. Diabetes Care, 22(9), pp.1561-1567.

- Di Cianni, G., et al. (2003). Intermediate metabolism in normal pregnancy and in gestational diabetes. Diabetes/metabolism research and reviews, 19(4), pp.259-270.

- Stapleton, A., 2002. Urinary tract infections in patients with diabetes. The American journal of medicine, 113(1), pp.80-84.

- NICE. (2021). Erectile dysfunction.

- Boston University School of Medicine. (2021). Epidemiology of ED. https://www.bumc.bu.edu/sexualmedicine/physicianinformation/epidemiology-of-ed/ [Last accessed 15.09.21].

- NICE. (2021). Erectile dysfunction. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/erectile-dysfunction/ [Accessed 06.05.2022].

- Boston University School of Medicine. (2021). Epidemiology of ED. https://www.bumc.bu.edu/sexualmedicine/physicianinformation/epidemiology-of-ed/ [Last accessed 15.09.21].

- Yazdanpanah, L., et al. (2018). Incidence and Risk Factors of Diabetic Foot Ulcer: A Population-Based Diabetic Foot Cohort (ADFC Study)-Two-Year Follow-Up Study. International Journal Of Endocrinology, 7631659.

- Lin, C., Liu, J., & Sun, H. (2020). Risk factors for lower extremity amputation in patients with diabetic foot ulcers: A meta-analysis. PloS one, 15(9), e0239236.

- Paul D., et al. (2013) Association Among Depression, Physical Functioning, and Hearing and Vision Impairment in Adults With Diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum, 26 (1), pp. 6–15.

- Trikkalinou, A., et al. (2017). Type 2 diabetes and quality of life. World Journal of Diabetes, 8(4), pp. 120–129.

- Wang, B., An, X., Shi, X., and Zhang, J. (2017). Management of Endocrine Disease: Suicide risk in patients with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Endocrinology 177, 4, R169-R181.

- Sivaprasad S, et al. (2012) Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in various ethnic groups: a worldwide perspective. Survey of Ophthalmology. 57 (4) pp. 347-70.

- Calle, E.E., et al. (2002). The American cancer society cancer prevention study II nutrition cohort: rationale, study design, and baseline characteristics. Cancer, 94 (2), pp. 500-511.

- Steven, S., et al. (2016). Very Low-Calorie Diet and 6 Months of Weight Stability in Type 2 Diabetes: Pathophysiological Changes in Responders and Nonresponders, Diabetes Care, 39 (5).

- Son, J., et al. (2017). Low muscle mass and risk of type 2 Diabetes in middle-aged and older adults: findings from the KoGES. Diabetologia, 60 (5).

- Holten, M. K., et al. (2004). Strength training increases insulin-mediated glucose uptake, glut4 content, and insulin signaling in skeletal muscle in patients with type 2 diabetes, Diabetes, 53 (2), pp. 294-305.

- Aune, D., et al. (2015). Physical activity and the risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. European Journal of Epidemiology, 30 (7), pp. 529-542.

- Aune, D., et al. (2015). Physical activity and the risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. European Journal of Epidemiology, 30 (7), pp. 529-542.

- Mesarwi, O., et al. (2013). Sleep disorders and the development of insulin resistance and obesity. Endocrinology and metabolism clinics of North America, 42 (3).

- Tasali, E., Wroblewski, K., Kahn, E., Kilkus, J., & Schoeller, D. A. (2022). Effect of sleep extension on objectively assessed energy intake among adults with overweight in real-life settings: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine, 182 (4), pp. 365–374.