Getting older doesn’t have to mean getting weaker.

From our mid‑thirties onwards, we begin to lose muscle mass – especially if we are inactive – and by the age of 50, it can speed up. This age‑related muscle loss undermines your health and independence: weaker muscles mean reduced mobility, higher risk of falls and fractures, and declining quality of life.

Muscle strength is also a powerful predictor of longevity – how long and how well you’ll live. Meta‑analyses show that people in the lowest strength category have more than three times the risk of dying compared with those in the highest strength group [1]. Science tells us that low muscle strength in old age is a greater mortality risk factor than smoking, high blood pressure, and diabetes [2].

The good news is that strength is highly trainable at any age. Strength training is the best anti-ageing strategy there is for healthy ageing and longevity – and the sooner you start, the better. We’ve seen this first hand with thousands of personal training clients in their 40s, 50s, 60s, and beyond who have transformed their health and body composition at Ultimate Performance with structured training.

Building muscle through progressive resistance training can slow or reverse sarcopenia, improve your metabolic health, bolster bone and hormonal health, and even support your brain. In this article, we explain why muscle loss accelerates after 40, why it matters for your long‑term wellbeing, and how weight training offers a science‑backed solution to help you live better, longer.

Why muscle loss accelerates after 40

By your 40s and 50s, it becomes noticeably harder to stay lean or feel as strong as you once did. That isn’t just in your head – it reflects real physiological changes. Muscle mass declines roughly 3–5% per decade after age 30, and if you’re inactive this loss can accelerate to around 10% per decade after 50 [1]. This age‑related decline in muscle size and strength is known as sarcopenia. While it affects millions, it is not an irreversible destiny; much of it is driven by modifiable factors.

One major driver is lifestyle. Modern life encourages long hours of sitting and little physical exertion. Reduced exercise and activity signals your body that muscle is not needed, so it is broken down. Inadequate sleep, chronic stress and diets low in high‑quality protein exacerbate this decline. Scientific reviews list inactivity, insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, hormonal changes and a reduction in satellite cells as key contributors to muscle loss [1][19].

Hormonal shifts further compound the problem. From about age 40, men’s testosterone levels decline by roughly 1–2% per year, and over a third of men over 45 have levels below the normal range [18]. Testosterone supports muscle growth and bone health – lower levels mean less anabolic signalling and a greater tendency to store fat. Women experience a sharper drop in estrogen as production stops at menopause, after which bone and muscle loss can accelerate. Post‑menopausal women can lose 1–2% of bone density per year and up to 25% overall [3]. Declining estrogen is also linked to increased fat storage and reduced muscle quality. These hormonal changes affect recovery too – you may feel more fatigued between workouts and less resilient to stress.

Another factor is anabolic resistance – older muscle fibres become less responsive to the anabolic signals from exercise and protein intake. Small doses of amino acids that readily stimulate muscle protein synthesis in young adults produce a blunted response in older adults [2][4]. The cellular machinery responsible for muscle growth, including the mTOR pathway, becomes less sensitive with age [6]. In younger muscles, mTOR signals cells to build new proteins; in older muscles, that signal weakens, requiring more consistent and robust training stimuli to maintain and grow lean mass.

This interplay of inactivity, hormonal decline, inflammation and anabolic resistance explains why muscle mass and strength decline more rapidly after 40. The encouraging news is that these factors are modifiable. Regular resistance training, adequate protein intake, stress management and quality sleep can all counteract sarcopenia by stimulating muscle protein synthesis and modulating hormones and inflammation [1][2].

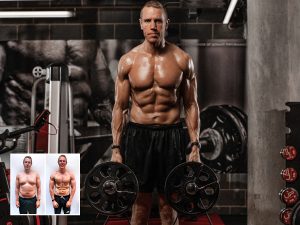

Read how company boss Scott built muscle over 7 weeks to achieve this incredible physique at 45

Why this matters

Muscle is known among some scientists as ‘the organ of longevity’ for a reason.

The gradual loss of muscle (sarcopenia) that begins in midlife can have dramatic consequences not just for your body composition, but for your metabolism, your healthspan, and your life expectancy. Why?

Because when you lose muscle, you lose your body’s most metabolically active tissue – the engine that burns calories and helps regulate blood sugar. With less muscle, your resting metabolism slows. You burn fewer calories, even at rest, which makes it far easier to gain fat, particularly around the abdomen. This internal, “hidden” fat – known as visceral fat – builds up around your organs such as the liver and pancreas. This kind of fat isn’t cosmetic – it releases inflammatory molecules that drive insulin resistance, increase blood pressure, and elevate your risk of heart disease, stroke and type 2 diabetes [4][19].

Muscle is one of your greatest defences against this process. It acts like a sponge for glucose, pulling sugar out of the bloodstream and keeping your insulin levels balanced. When muscle mass declines, this buffering system weakens – your blood sugar rises more easily after meals, and over time, your body becomes less efficient at managing energy. This shift towards insulin resistance is one reason many people in their 40s and 50s suddenly find they gain fat more easily, even when eating the same foods as before. Studies show that low muscle mass and strength are associated with a greater likelihood of developing insulin resistance, dyslipidaemia and metabolic syndrome [4][13].

Inactivity compounds the problem. The World Health Organisation classifies physical inactivity as one of the top four causes of premature death worldwide, contributing to roughly 1 in 10 deaths from chronic disease [23]. When you stop using your muscles, your metabolism slows further, your cardiovascular fitness declines, and the risk of developing lifestyle diseases climbs sharply.

The effects reach far beyond metabolism. Losing strength and mobility directly threatens independence. Everyday tasks, such as carrying shopping, climbing stairs, standing up unaided from a chair, all become harder. Balance deteriorates, falls become more likely, and injuries take longer to heal. Fractures, particularly hip fractures, can trigger a downward spiral of reduced movement and rapid health decline [5][16]. In contrast, maintaining strength means maintaining freedom – the ability to move confidently, stay active, and enjoy life on your own terms well into later years.

Scientists now refer to the combination of low muscle and high fat as sarcopenic obesity – a potent mix that worsens every marker of metabolic and cardiovascular health. Studies consistently show that weaker adults face more than three times the risk of dying early compared to their strongest peers, regardless of age or weight. In other words, muscle strength predicts how long you’ll live just as powerfully as smoking or blood pressure – and unlike genetics, it’s entirely within your control [17].

Preserving muscle is one of the most effective things you can do to protect your health span – the years you live strong, capable and free from disease. Strength training reverses these trends: it rebuilds lost muscle, increases your base metabolic rate, improves blood sugar control, and reduces the amount of inflammatory and harmful visceral fat you carry around your middle.

Read why weight training has proved to be a ‘fountain of youth’ for Sybil at the age of 68.

The science of weight training for strength, hormones, bones and brain health

Regular resistance training in midlife isn’t just about looking better – it can literally turn back the clock on many markers of ageing. Here are some of the most important benefits, backed by scientific research:

Longevity and disease prevention

Strength training is a powerful longevity tool. Large-scale reviews have demonstrated that adults who incorporate resistance work see a significant reduction in all-cause mortality – in some cases, a 20–30% drop compared to those who do no strength work at all [7]. When combined with aerobic training, the protective effect is even stronger. Resistance exercise is also linked to lower risks of cardiovascular disease, cancer and metabolic diseases [4][7]. In short, strength training and the way it preserves and builds muscle is a proven, actionable way to extend your lifespan and safeguard your health.

More muscle, strength and mobility

While adults naturally lose muscle mass and strength as they age, resistance training is shown to be an incredibly effective way to slow down and even reverse this process. Studies show that even in your 50s, 60s and beyond, your body retains the ability to build muscle tissue with the right training stimulus [6][13]. In fact, older trainees can achieve comparable muscle growth to younger adults with proper training and nutrition [6].

One of the most striking examples comes from a landmark 1990 study at Tufts University, where frail adults aged 86–96 performed high‑intensity strength training three times per week. After just 8 weeks, participants doubled their strength (113% increase), gained 9% in thigh muscle size, and walked faster and more confidently – with some regaining the ability to stand and walk independently [5]. This proved that muscle loss is not an irreversible feature of ageing, but something that can be dramatically improved with resistance training.

More muscle means better functional ability in daily life – things like climbing stairs, carrying groceries or playing with your kids and grandkids become easier. Strength training literally helps you ‘use it’ instead of ‘lose it’ when it comes to your muscles and mobility.

Stronger bones

Lifting weights doesn’t just strengthen muscles – it also strengthens your bones. Resistance training places healthy stress on bones, which stimulates them to become denser and more resilient. This is critical as we age. Post-menopausal women in particular face a higher risk of osteoporosis and fractures due to bone density loss. High-intensity weight training has been shown to significantly increase bone mineral density and improve physical function in women with low bone mass [3]. Even men in their 60s and 70s can improve bone health through lifting [2][10].

Better metabolic health

Muscle is the body’s primary “sink” for glucose disposal. When you have more muscle, your body can more effectively clear glucose from the bloodstream, improving insulin sensitivity and preventing fat accumulation [4][20]. As you lose muscle, your resting metabolic rate drops, meaning your body burns fewer calories even at rest. That shift lets fat, particularly dangerous visceral fat, accumulate more easily. As we spoke about earlier, visceral fat resides deep around abdominal organs (liver, kidneys, intestines), where it secretes inflammatory molecules and disrupts metabolic regulation. The combination of reduced muscle and rising visceral fat fosters insulin resistance, worsening blood sugar control, and increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia and cardiovascular disease [19].

One study found that just two sessions of weight training per week for 16 weeks significantly improved insulin sensitivity and reduced abdominal fat in men around 65 with type 2 diabetes [4].

Many clients in their 40s and 50s find that incorporating strength training helps reverse “middle-age spread,” lowers their blood glucose, and reduces risk factors for metabolic syndrome. Building muscle is a powerful insurance policy for your health as you age.

Sharper brain function and cognition

Want to stay mentally sharp into old age? Emerging research shows that strength training can improve cognitive function and mental health in older adults [6][5]. In fact, resistance training appears to be one of the most effective exercise modalities for preserving brain health. Studies have found improvements in memory, executive function (decision-making) and even mood among seniors who lift regularly [5]. Weight training may stimulate the release of growth factors like BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) and improve blood flow to the brain, which supports the growth of new neurons and synapses. Coupled with improved sleep, reduced inflammation and more stable blood sugar, strength training becomes a potent tool to preserve cognitive function, slow mental ageing, and support emotional well-being well into later life.

Hormonal health

Ageing changes the hormonal environment, but strength training helps your body stay responsive to those signals. After a hard session, some anabolic hormones such as testosterone and growth hormone rise briefly for up to 48 hours, yet these short-term spikes are not the main driver of progress [11][12]. The lasting benefits come from stronger muscles, better insulin sensitivity, and improved metabolic function.

For women, particularly during and after menopause, resistance training cannot restore oestrogen levels, but it can offset the consequences of that loss – protecting bone, maintaining lean tissue, and supporting mood and energy [3][21].

For men, strength training helps preserve muscle, metabolic health, and hormonal responsiveness. It does not permanently raise testosterone, but by improving body composition, sleep, and stress balance, it supports a healthier overall endocrine profile [18][12].

In both cases, lifting weights makes your body more robust in a lower-hormone environment. It’s not hormone replacement – it’s a way to keep the system resilient.

In short, weightlifting after 40 is the closest thing to a real-life fountain of youth. It targets nearly every concern of ageing – weakness, fragility, slow metabolism, cognitive decline, and more. And unlike any pill or quick fix, the results of strength training are long-lasting and life-changing. Many clients at Ultimate Performance report better energy, libido, mood and body composition once strength training becomes a staple in their routine.

How to train through menopause and andropause

Hormonal changes in midlife can have a significant impact on how your body responds to training. For women, the transition through menopause (usually in your late 40s to early 50s) brings steep drops in estrogen and progesterone. For men, “andropause” is a gradual decline in testosterone typically starting in the late 30s and 40s. Both of these shifts can affect recovery, muscle retention, fat distribution, mood and energy levels [21][18]. The key point, however, is that hormonal changes are not a reason to give up – they’re actually a compelling reason to start (or continue) training. A properly structured exercise and nutrition regimen can counteract many of the unwanted effects of menopause or andropause.

Training through menopause (Women)

Menopause is often accompanied by a range of physical and psychological symptoms, and many women see increased abdominal fat storage, reduced bone density, muscle loss, fluctuating mood and persistently low energy. Falling oestrogen disrupts everything from bone turnover to metabolic rate and mood [3][21]. Load‑bearing strength training is one of the most effective ways to fight back, because lifting weights stimulates muscle and preserves bone mass that would otherwise decline rapidly after menopause. Twice‑weekly sessions of heavy lifts (such as deadlifts, squats and presses) combined with moderate impact work have been shown to increase lumbar spine and femoral neck bone density and improve functional strength in post‑menopausal women [3].

At U.P., we tailor training intensity and volume to how you’re feeling week to week, rather than prescribing blanket low‑intensity workouts. Many women respond well to shorter sessions with challenging weights, interspersed with low‑impact daily activity, such as walking to support fat loss and recovery. We also emphasise stress management and restorative sleep because declining progesterone and estrogen reduce the body’s resilience to physical and emotional stress[21]. Training helps offset this by improving mood and sleep quality.

High‑intensity cardio sessions aren’t off‑limits, but they should be used judiciously – when energy and recovery allow – so as not to overload the nervous system. Finally, the structure and accountability of a personalised programme are key during menopause. Our coaches plan each session, monitor nutrition and recovery, and adjust workload as your symptoms fluctuate. That way, you don’t have to guess whether you’re doing the right thing – you just follow the plan and trust the process. This support not only improves body composition and metabolic health but also provides a vital boost to confidence and resilience, allowing women to thrive during and after menopause.

Training through andropause (Men)

Andropause – often described as the male equivalent of menopause – is the gradual decline in testosterone and other hormones that begins for many men in their late thirties and continues through midlife. Unlike the sudden hormonal drop women experience, this is a slow drift that can leave men feeling less energetic, with more abdominal fat, slower recovery, and a harder time maintaining muscle. These changes aren’t inevitable decline – they’re signals that your body needs a stronger training and recovery framework.

At U.P., the approach for men in their forties and fifties isn’t drastically different from what we use with younger clients – it’s simply more deliberate. We focus on smart, high-quality strength training that stimulates muscle growth without overwhelming recovery capacity. Most male clients train three to four times per week using full-body or upper-lower splits built around big, multi-joint compound movements: squats, presses, rows, and deadlifts. This ensures every major muscle group is trained multiple times per week to maximise muscle protein synthesis and improve coordination and resilience across the whole body.

Because recovery capacity declines with age, we balance intensity with adequate rest. Moderate-to-heavy loads in the 8–12 rep range provide an optimal mix of muscle tension and joint friendliness. We often programme accumulation-focused phases – steady, volume-based training aimed at hypertrophy and endurance—interspersed with shorter intensification blocks for strength. Superset pairings and controlled tempos help maintain training density without unnecessary joint stress. The goal is progress without grinding the body down.

Conditioning is another key pillar. As aerobic fitness and VO₂ max can naturally decline with age, we include structured conditioning sessions to build cardiovascular health, enhance recovery between workouts, and support long-term metabolic health. Together, this combination of strength, conditioning, and recovery strategies helps men preserve lean mass, sustain healthy body composition, and maintain vitality well into their 50s and 60s.

In summary, whether you’re male or female, don’t use midlife hormonal changes as an excuse to back off. If anything, it’s motivation to be more proactive. Strength training, paired with smart lifestyle choices, is your ally to make it through menopause or andropause with far fewer negatives.

Conclusion

Ageing doesn’t have to mean decline. The science is clear – muscle and strength are among the strongest predictors of how long and how well you’ll live. Losing them accelerates every marker of ageing: slower metabolism, poorer balance, lower energy, and greater risk of disease. Building them does the opposite.

Strength training is the most powerful tool we have to protect health and independence for life. It keeps your metabolism efficient, your bones and joints resilient, and your mind sharp. And it’s never too late to start – muscle responds to resistance training at any age.

What matters is consistency, intelligent programming, and the right level of challenge. That’s where expertise makes all the difference. At Ultimate Performance, we’ve helped thousands of men and women in their 40s, 50s, and beyond rebuild strength, vitality and confidence through data-driven, results-focused personal training.

If you want to future-proof your body and see what you’re truly capable of, start by building strength. And if you want the world’s most experienced team to guide you through it, we’re here to help you begin.

FAQs on weight training over 40

How much protein do I need to build muscle after 40?

Most people over 40 should aim for roughly 1.6–2.2 grams of protein per kilogram of bodyweight per day to optimise muscle gain and recovery [1][2]. If you’re in a caloric deficit (trying to lose fat) or training very hard, stick to the higher end of that range (around 2.0–2.2 g/kg). For example, an 80 kg person would target about 130–175 g of protein daily. It’s best to spread this across 3–5 meals per day for maximal muscle protein synthesis. Adequate protein becomes even more crucial as you age because your muscles can be slightly less responsive to protein intake (a phenomenon called “anabolic resistance”) [1] – but hitting these targets helps overcome that. Lean meats, fish, eggs, low-fat dairy, and protein shakes are all convenient protein sources.

Will lifting weights make me bulky?

No – this is one of the biggest myths, especially among women. Building big “bodybuilder” muscles requires years of very specific training, a calorie surplus, and often genetic predisposition (and that’s for younger folks, too). For people in their 40s and 50s, weight training will do the opposite of making you bulky – it will help you lose fat and increase muscle firmness, giving you a leaner, tighter physique. Think of it this way – muscle is denser and takes up less space than fat. So if you swap 5kg of fat for 5kg of muscle, you get smaller and firmer, not bigger. Our female clients universally become more shapely and defined, not masculine or bulky. And our male clients end up looking athletic and cut, not swollen. So don’t worry – lifting will sculpt your body, not blow it up.

Can I really build muscle in my 40s and 50s? Isn’t it all downhill?

Yes, you absolutely can build muscle, even if you’ve never trained seriously before. Studies on middle-aged and older adults show significant gains in lean muscle tissue with consistent resistance training and adequate protein intake [2][6]. In fact, because weight training may be a new stimulus, many over-40 beginners see rapid improvements in strength and muscle in their first 6-12 months – sometimes outpacing younger folks who’ve already been training. You might find you need a bit more recovery between hard sessions (e.g. training body parts every 3-4 days instead of every couple of days like a 20-year-old might), but the muscle-building machinery still works. We have clients in their 50s hitting personal bests in strength, and building muscle. The key is consistency – it might take a little longer to see dramatic changes compared to your 20s, but month after month, you will notice your body getting stronger and more muscular. Patience and persistence win.

Do I need to take protein shakes or supplements?

Protein shakes are convenient, not magical. You do not need them if you can meet your protein requirements through whole foods. However, many people find it challenging to eat, say, 150g-plus of protein through chicken, fish, eggs, etc. every single day. That’s where a quality whey or plant-based protein powder can help – it’s a low-calorie, high-protein boost that’s quick to consume (for example, a scoop in water can provide ~25 g protein). Especially post-workout, a shake can be an easy way to kickstart recovery if you don’t have a meal immediately available [1][20]. Other supplements that can be beneficial for over-40 lifters include creatine (for strength and muscle maintenance), vitamin D (for bone and hormone health), and omega-3 fish oils (for joint health and reducing inflammation) [20]. But remember, supplements are only the cherry on top. The foundation is a solid diet and training program. No powder or pill can replace progressive training, sufficient protein, and proper rest.

Is weight training safe for my joints?

When done correctly, weight training is one of the best things you can do for your joints. It strengthens the muscles, tendons, and ligaments that support your joints, improves joint stability (as we covered in Rule 6), and can even stimulate production of joint lubricating fluids. Many common aches – like knee pain or back pain – actually improve when you strengthen the surrounding musculature. The caveat is that you must use good form and sensible progressions. Poor technique, ego lifting, or not warming up – those can injure joints, but that’s due to human error, not an indictment of weight training itself. If you’re careful to learn proper movements and you don’t do anything crazy (like max squat without ever squatting before), you will find your joints get more resilient over time. In fact, several of our older clients have been able to discontinue knee or back pain medications after a few months of training, because their bodies are functioning better. Always communicate with your trainer about any existing issues, and they can customise exercises for you. But rest assured, motion is lotion for the joints – staying active and strong is far better than becoming sedentary and letting joints deteriorate.

References

- Breen L, Phillips SM (2011). Skeletal muscle protein metabolism in the elderly: Interventions to counteract the “anabolic resistance” of ageing. Nutrition & Metabolism, 8:68[1].

- Churchward-Venne TA, Burd NA, Phillips SM (2012). Nutritional regulation of muscle protein synthesis with resistance exercise: strategies to enhance anabolism. Nutrition & Metabolism, 9(1):40[2].

- Cuervo AM (2008). Autophagy and aging: keeping that old broom working. Trends in Genetics, 24(12):604–612[3].

- Dideriksen K, Reitelseder S, Holm L (2013). Influence of amino acids, dietary protein, and physical activity on muscle mass development in humans. Nutrients, 5(3):852–876[4][5].

- Fiatarone MA, Marks EC, Ryan ND, et al. (1990). High-Intensity Strength Training in Nonagenarians: Effects on Skeletal Muscle. JAMA, 263(22):3029–3034[6].

- Fry CS, Glynn EL, Drummond MJ, et al. (2010). Blood flow restriction exercise stimulates mTORC1 signaling and muscle protein synthesis in older men. Journal of Applied Physiology, 108(5):1199–1209[7].

- Fujita S, Rasmussen BB, Cadenas JG, et al. (2007). Aerobic exercise overcomes the age-related insulin resistance of muscle protein metabolism by improving endothelial function and Akt/mTOR signaling. Diabetes, 56(6):1615–1622[8].

- Greiwe JS, Cheng B, Rubin DC, Yarasheski KE, Semenkovich CF (2001). Resistance exercise decreases skeletal muscle tumor necrosis factor α in frail elderly humans. FASEB Journal, 15(2):475–482[9].

- Hardee JP, Porter RR, Sui X, et al. (2014). The effect of resistance exercise on all-cause mortality in cancer survivors. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 89(8):1108–1115[10].

- Kerr D, Ackland TR, Maslen BA, Morton AR, Prince RL (2001). Resistance training over 2 years increases bone mass in calcium-replete postmenopausal women. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 16(1):175–181[12].

- Kraemer WJ, Ratamess NA (2005). Hormonal responses and adaptations to resistance exercise and training. Sports Medicine, 35(4):339–361[13].

- Kraemer WJ, Häkkinen K, Newton RU, et al. (1999). Effects of heavy-resistance training on hormonal response patterns in younger vs. older men. Journal of Applied Physiology, 87(3):982–992[14].

- Kumar V, Selby A, Rankin D, et al. (2009). Age-related differences in the dose–response relationship of muscle protein synthesis to resistance exercise in young and old men. Journal of Physiology, 587(1):211–217[15].

- Lang CH, Frost RA, Nairn AC, MacLean DA, Vary TC (2002). TNF-α impairs heart and skeletal muscle protein synthesis by altering translation initiation. American Journal of Physiology – Endocrinology and Metabolism, 282(2):E336–E347[18].

- Milman S, Atzmon G, Huffman DM, et al. (2014). Low insulin-like growth factor-1 level predicts survival in humans with exceptional longevity. Aging Cell, 13(5):769–771[19].

- Phillips MD, Patrizi RM, Cheek DJ, et al. (2012). Resistance training reduces subclinical inflammation in obese, postmenopausal women. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 44(11):2099–2110[20].

- Ruiz JR, Sui X, Lobelo F, et al. (2009). Muscular strength and adiposity as predictors of adulthood cancer mortality in men. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 18(5):1468–1476[21].

- Sato K, Iemitsu M, Matsutani K, et al. (2014). Resistance training restores muscle sex steroid hormone steroidogenesis in older men. FASEB Journal, 28(4):1891–1897[24].

- Sikora E, Scapagnini G, Barbagallo M (2010). Curcumin, inflammation, ageing and age-related diseases. Immunity & Ageing, 7:1 (pp.1–4)[25].

- Smith GI, Atherton PJ, Reeds DN, et al. (2011). Dietary omega-3 fatty acid supplementation increases the rate of muscle protein synthesis in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 93(2):402–412[26].

- Taku K, Melby MK, Kronenberg F, Kurzer MS, Messina M (2012). Extracted or synthesized soybean isoflavones reduce menopausal hot flash frequency and severity: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Menopause, 19(7):776–790[27].

- Toth MJ, Matthews DE, Tracy RP, Previs MF (2005). Age-related differences in skeletal muscle protein synthesis: relation to markers of immune activation. American Journal of Physiology – Endocrinology and Metabolism, 288(5):E883–E891[28].

- World Health Organization (2009). Global Health Risks: Mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. WHO Press, Geneva[29].

- Woods JA, Wilund KR, Martin SA, Kistler BM (2012). Exercise, inflammation and aging. Aging and Disease, 3(1):130–140[31].